(Source)

The first suggestions that Andrew Johnson should be impeached were raised less than a week into his term as Vice President. On the morning of March 4, 1865, when he was to be sworn into office alongside President Abraham Lincoln, Johnson was suffering from typhoid fever. Meeting his his predecessor, Hannibal Hamlin, he drank a few whiskeys to try to combat the illness.

He apparently had a few too many. By the time Johnson was to give a brief address to the Senate, he was considerably drunk. Slurring his words, he delivered a rambling, incoherent, and overlong address boasting about his humble beginnings and his ultimate triumph over the Southern aristocrats who had looked down on him. At one point, Hamlin even pulled on Johnson's coattails in a futile effort to make him stop talking. After he finally wrapped up the address and took the oath of office, Johnson became so confused with his duty of swearing in the new senators that he turned the task over to a clerk.

The spectacle was all the more embarrassing because it came shortly before Lincoln's stately second inaugural address, which has endured as one of the great speeches of the Civil War. Senators were horrified by Johnson's performance; Senator Zachariah Chandler, a Republican from Michigan, recorded in his diary, "I was never so mortified in my life, had I been able to find a hole I would have dropped through it out of sight." Johnson was ridiculed in the press, with one article labeling him a "drunken clown."

Although Johnson showed no other signs of alcoholism beyond this public display, the speech led to rumors that he was a dipsomaniac. These gained further traction when Johnson, still suffering from typhoid fever, left the Senate for a few days. When he returned on March 11, there were suggestions that he had gone on a chaotic drinking spree. Some Republicans drafted a resolution calling for him to resign, and there was talk of impeachment as a way to remove him from the second highest office in the land.

Lincoln urged his colleagues to be calm, saying his Vice President was still getting accustomed to the job. "It has been a severe lesson for Andy, but I do not think he will do it again," he said.

Just a month later, Lincoln's reassurance would be put to the test as Johnson became President of the United States. Unfortunately, a rift between Johnson and the liberal wing of the Republican Party would quickly deepen, culminating in the first impeachment trial to affect a President of the United States.

Early life

Johnson was born in Raleigh, North Carolina, on December 29, 1808. His father died when he was three years old, and seven years later he was apprenticed to a tailor named James Selby. After working for Selby for five years, Johnson abruptly abandoned the apprenticeship after a neighbor threatened to sue him and his brother, William, for throwing pieces of wood at her house.

Running away to South Carolina, Johnson worked for another tailor for two years. Here he fell in love with a girl and asked her to marry him, but her family objected to the pairing. Dejected, Johnson returned to Raleigh and asked Selby to take him back in. Although Selby had posted notices offering a reward for Johnson's return, he now refused the young man's request.

A notice posted by Selby seeking the return of Andrew Johnson and his brother (Source)

Johnson subsequently moved to Greenville, Tennessee, with his mother and stepmother. Assisted by his wife Eliza, whom he married in 1827, he began a self-education effort. He had also learned enough about the tailoring business to start his own business.

Before long, Johnson had entered politics. He was elected a town alderman in 1829, and as mayor of Greenville in 1834. He joined the state militia around the same time, winning the nickname of "Colonel Johnson" after achieving this rank. Johnson served in the Tennessee house of representatives from 1835 to 1837 and again from 1839 to 1841, when he was elected to the state senate. During his political career, he helped write a new state constitution that eliminated the property-owning requirement to vote or hold office.

Running as a Democrat in 1842, Johnson was elected to the first of five terms in the U.S. House of Representatives. In this chamber, he came out against a number of spending initiatives including increases to soldiers' pay, accepting funds to start the Smithsonian Institution, infrastructure projects in the nation's capital, and funding to aid the victims and families of a cannon explosion on the USS Princeton that had killed eight people, including two Cabinet officials. Johnson was also opposed to plantation rule and protective tariffs. However, he did express support for the public funding of education.

These stances hint at Johnson's deep-seated hatred for the wealthy elite. He despised any organizations or people he saw as aristocratic, including military academies and future Confederate president Jefferson Davis, whom he said was part of the "illegitimate, swaggering, bastard, scrub aristocracy."

A depiction of Andrew Johnson in 1842, the year he was first elected to the House of Representatives (Source)

Some racist remarks are attributed to Johnson around this time. In 1844, he tacitly supported slavery by declaring that a black man was "inferior to the white man in point of intellect, better calculated in physical structure to undergo drudgery and hardship." His business was also successful enough that he bought a few slaves of his own. He proclaimed himself to be equally critical of both abolitionist and the most virulent pro-slavery plantation owners, saying both were driving the country toward war instead of reconciliation.

When it looked like a gerrymandering effort would threaten his seat in the House, Johnson ran for governor of Tennessee and was elected in 1852. His signature accomplishment during his time in office was the establishment of the first state law supporting public education through taxation. Although he won re-election against Know-Nothing candidate Meredith P. Gentry in 1856, he soon left the governor's office when the state legislature named him to the U.S. Senate.

During his time in the state house of representatives, Johnson had proposed a homestead bill to help Tennessee's poor residents acquire land to cultivate. He made a similar proposal in the Senate, advocating a bill to provide 160-acre plots. Although this bill passed in 1860, it was vetoed by President James Buchanan. Johnson would persist, pushing through the homestead bill in 1862.

Civil War

The long simmering tensions between the North and South finally came to a head in the election of 1860. Fearing that Lincoln would destroy the slave-based economy of the Southern states, many political figures below the Mason-Dixon Line threatened that secession would follow if the Republican candidate was elected President. Johnson sought to strike a balance, throwing his support behind Southern Democratic candidate John C. Breckinridge. He also opposed secession and urged Tennessee to remain in the Union if Lincoln came to office.

Breckinridge swept the Southern states, but came far short of Lincoln's electoral total. As calls for secession increased, Johnson continued to advocate for unity. On December 18, just two days before South Carolina became the first state to break away, Johnson pleaded, "Let us exclaim that the Union, the Federal Union, must be preserved!"

The attack on Fort Sumter prompted more states to secede. Johnson traveled throughout Tennessee, making public appearances urging the state to remain loyal to the Union. It was a risky move; despite Johnson's status as an elected official, his stance on secession had become quite unpopular. Across the state, he was burned and shot in effigy. In one instance, Johnson's train was stopped by an angry mob out to lynch the senator; he was reportedly saved only at the intervention of Jefferson Davis. At one appearance, he responded to an angry and hostile crowd by calmly taking a pistol out of his pocket, placing it on the pulpit where it could be quickly taken up at the first sign of trouble, and continuing his address.

Johnson's efforts were for naught. Tennessee voted to secede on June 8, 1861, becoming the last state to leave the Union. Although elected officials typically withdrew from Congress after the secession of their state, Johnson was the only senator from the South to keep his seat. This show of support for the Union made him a popular figure in the North, but he was forced to live in Washington, D.C., to avoid being arrested in Tennessee. Although Eliza continued to live in Greeneville for a time, she too eventually moved to the nation's capital.

The exile was fairly short-lived. After Union troops captured Nashville on March 4, 1862, Lincoln named Johnson to be the state's military governor and awarded him the rank of brigadier general. Resigning from the Senate to take on this duty, Johnson returned to Tennessee to find that the Confederacy had branded him an "enemy alien," subsequently confiscating and selling his property.

Johnson was faced with considerable challenges in his role as military governor of Tennessee. He seized the Bank of Tennessee and records left behind by the fleeing Confederate government, reorganized the Nashville city government, and silenced secessionist newspapers. The Confederacy continued to hold portions of the state and made frequent raids into Union-held territory. In 1863, he was embarrassed when a civil election named a conservative pro-slavery candidate to succeed him. On Lincoln's orders, Johnson ignored the result. He also issued a requirement that Tennessee residents needed to take a loyalty oath to the Union in order to vote, and even then would have to wait six months before casting a ballot.

While governor, Johnson showed more sympathy to the idea of emancipating slaves. But he considered this to be more of a military measure, one which would help end the war by taking valuable resources from the aristocratic plantation owners who had encouraged the war. "Treason must be made odious and traitors punished," he declared at one point. At Lincoln's urging, he worked to incorporate black soldiers into Tennessee regiments to defend against Confederate raids, although these troops never received enough arms or support to become a reliable force.

With the presidential election of 1864 looking to be a particularly close one, the Republicans chose Johnson as a compromise candidate for Vice President to replace Hannibal Hamlin. During the campaign, Johnson also continued to show some resentment for the aristocrats. At one stop in Logansport, Indiana, he noted how his Democratic opponents had laughed him off as a "boorish tailor." Johnson said he took it as a compliment, since it showed how he had risen from humble roots to a successful political career. He held the principle that "if a man does not disgrace his profession, it never disgraces him." In one address, he cited certain plantation owners by name and suggested that the nation would be improved if their land was broken up into smaller plots worked by "loyal, industrious farmers."

Johnson also demonstrated more support for the idea of ending slavery. "Before the rebellion, I was for sustaining the Government with slavery; now I am for sustaining the government without slavery, without regard to a particular institution," he declared in an address at Louisville, Kentucky on October 13, 1864. "Institutions must be subordinate, and the Government must be supreme." In same address, says he supports "the elevation of each and every man, white and black, according to his talent and industry."

Eleven days later, Johnson emancipated Tennessee's slaves. This action, again taken at Lincoln's urging, was essentially a voluntary one; since Tennessee had come under control of the Union at the time the Emancipation Proclamation had been issued, it was not considered to be in rebellion and its slaves had not been freed by the order. Johnson seemed particularly happy with emancipaction; on the same day he approved the action, he told a black audience in Nashville, "I will indeed be your Moses, and lead you through the Red Sea of war and bondage to a fairer future of liberty and peace."

Johnson even wanted to delay his inauguration until April so he could oversee the emancipation process in Tennessee, but Lincoln insisted that he be sworn in on schedule. Historians have noted that it was fortunate that Johnson agreed to take office when he did. If the office of Vice President was vacant at the time Lincoln was assassinated, the presidential succession may have been thrown into limbo.

Accession to President

On the evening of April 14, 1865, Johnson was woken and informed that Lincoln had been shot. The President lingered through the night before passing away the next morning. After scarcely a month as Vice President, Johnson was given the oath of office by Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase and became the 17th President of the United States.

An illustration showing Johnson being sworn in as President (Source)

It soon emerged that John Wilkes Booth, Lincoln's assassin, was one of several conspirators aiming to kill a number of high-ranking Union officials in a coordinated assault. Johnson himself had been one of the targets; George Atzerodt had registered at his hotel and, after drinking plenty of alcohol, got cold feet and left without attempting to assassinate Johnson. Atzerodt was arrested soon after, and was one of four conspirators hanged for their role in the plot.

Shortly before his attack on Lincoln, Booth learned of Atzerodt's failure and made a last-ditch effort to frame Johnson as being part of the plot. He left a card for the Vice President with the message, "Don't wish to disturb you. Are you still at home? J. Wilkes Booth." However, this card was instead picked up by Johnson's secretary, who had met Booth after one of his performances and mistakenly thought the card was for him.

Although the process of the disbanding and surrender of Rebel armies was ongoing at the time of Lincoln's death, the Confederacy had essentially ceased to exist. Robert E. Lee had surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia five days before Lincoln was shot, and Jefferson Davis would be captured by Union troops about a month later. Johnson was enraged by the conspirators' attack on the Union government, and for a time seemed bent on revenge. He considered pursuing treason charges against the former Confederate military and political leaders, and was only dissuaded at the urging of Ulysses S. Grant.

This pugnacious attitude helped convince the Radical Republicans that Johnson would be a helpful ally in the postwar Reconstruction era. This political faction would be defined by their pursuit of full emancipation and civil rights for ex-slaves. They had been somewhat disappointed by Lincoln's support of gentler forms of repatriation and occasional hindrance of larger reforms. For example, he opted not to sign the Wade-Davis Bill to enforce Reconstruction efforts with federal troops and readmit Southern states only after they agreed to protect the rights of freedmen; instead, he killed the 1864 legislation with a pocket veto.

Senator Ben Wade, a Radical Republican from Ohio and a co-sponsor of the Wade-Davis Bill, declared to the new President, "Johnson, we have faith in you. By the gods, there will be no trouble now in running this government." Such feelings would be short-lived.

Falling out with the Radicals

On May 29, 1865, Johnson issued two proclamations outlining his plans for Reconstruction. The first issued a pardon and a promise of amnesty for any ex-Confederates who were willing to take an oath of loyalty to the Union and pledge to support the emancipation of slaves in the South. He also named William W. Holden as the provisional governor of North Carolina and directed him to amend the state constitution. Similar proclamations were made for other Confederate states, but made no request for a change in voting rules. This meant that black men were still excluded from the ballot box.

In one area, Johnson seemed keen to levy some punishment on the former Confederates. The wealthiest landowners in the South, namely those with estates worth $20,000 or more, would be required to seek individual pardons. It seemed clear that Johnson was relishing the opportunity to have the high and mighty aristocrats groveling before him for forgiveness. Even with this condition, Johnson still agreed to return the land of most plantation owners who made an appeal and grant them a pardon.

Most notably, Johnson failed to intercede when the South made blatant efforts to return Confederate officials to power. The Confederate vice president, along with four generals and five colonels from the Confederate army, were all elected to Congress after the war. Johnson also took no actions when Southern governments began imposing stringent "black codes" to strip the civil rights of black citizens. These included vagrancy laws to have idle black residents arrested and put to work; in short, a de facto form of slavery.

There were signs that whatever support Johnson may have had for emancipation and equality had cooled. He told one group of African-Americans, "The time may soon come when you shall be gathered together in a clime and country suited to you, should it be found that the two races cannot get along together." His private secretary, William G. Moore, recorded that Johnson displayed a "morbid distress and feeling against negroes." In a December 1867 message to Congress, he would remark that "negroes have shown less capacity for government than any other race of people" and were more likely to "relapse into barbarism."

Some historians have suggested that Johnson was not trying to impede the progress of ex-slaves so much as he was trying to keep any Reconstruction efforts within the boundaries set by the Constitution. In his veto of the Civil Rights Act, he said it "contains provisions which I can not approve consistently with my sense of duty to the whole people and my obligations to the Constitution of the United States." When he vetoed a bill to extend the mission of the Freedmen's Bureau, which was assisting former slaves displaced in the wake of emancipation, Johnson reasoned that it was federal encroachment on a state issue and an improper use of the military during peacetime; he also argued that it would hinder ex-slaves from being able to sustain themselves, and said there were no similar provisions for poor white men who had been harmed by the war.

An 1866 political cartoon depicts Johnson using a veto to boot the Freedmen's Bureau (Source)

Johnson agreed with the Radical Republicans on some issues. In particular, he thought that some individual rebels should be punished and that new state governments established in the South should meet certain conditions before the states were formally reabsorbed into the Union. However, he also thought that some of the proposed Reconstruction programs would benefit landowners more than freedmen.

The Radical Republicans were less than pleased at Johnson's acquiescence to the status quo in the South. The former Confederate states were quick to return ex-Confederates to power, some before they had even received a pardon. The political faction was also appalled when, in the summer of 1865, Johnson ordered the Freedmen's Bureau to return abandoned plantation lands to their former owners. In several cases, these lands had already been divided up and distributed to former slaves. While Johnson had originally been welcomed as a leader who would deal firmly with the rebellious states, he was now praised among Southern Democrats as a President who would protect them against the Republican agenda and preserve white supremacy in the region.

At the end of the year, Johnson declared that the work of Reconstruction was complete. The Radical Republican resistance mobilized quickly. Led by Representative Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, they refused to recognize members of Congress sent by states who had seceded from the Union. They also created a Joint Committee on Reconstruction, which began working on the Fourteenth Amendment to prevent Southern states from getting a numerical advantage in Congress by excluding black residents from the population count if they weren't allowed to vote.

In a President's Day message in 1866, Johnson complained that the committee was concentrating the government power accompanying Reconstruction into a tiny fringe group. He also said this approach would make the more moderate and conservative Republicans less likely to support his administration.

Radical Republicans passed the Civil Rights Bill of 1866 in the spring, targeting the black codes in the South and granting citizenship to anyone born in the United States. Johnson vetoed the legislation, saying it was "made to operate in favor of the colored and against the white race." In the first instance of Congress overriding a veto on a major piece of legislation, and by a margin of a single vote in the Senate, Congress overrode the veto to enact the bill. During his time in office, 15 of Johnson's 29 vetoes would be overturned, the most of any U.S. President. These bills included statehood for Nebraska and voting rights of black residents of Washington, D.C.

The most noticeable split between Johnson and the Radical Republicans occurred after he opposed ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment. Although he was distrusted by both Democrats and Republicans, the President tried to rally moderate members of both parties in a separate Union Party before the 1866 elections. During a "swing around the circle" campaign to rally support for this effort, he frequently traded insults with hecklers and made embarrassing statements; in one, he suggested that divine intervention had removed Lincoln from office so he could ascend to the White House. After this disastrous campaign, Republicans easily won majorities in both houses of Congress.

Once the new Congress was sworn in, they quickly passed the Reconstruction Act. This legislation divided the former Confederate states into five military districts and installed new governments to oversee the process of bringing the South back into the Union. Johnson vetoed the bill, but the Radical Republican majority easily overturned it.

Another bill passed over the President's veto was the Tenure of Office Act, which made it illegal for the President to dismiss any appointees who had been approved by the Senate without first getting Senate approval. This bill was essentially an effort to head off any effort Johnson might make to dismiss Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, a Lincoln appointee who was allied with the Radical Republicans, and replace him with someone who would guide the military element of Reconstruction in a way that was more in line with Johnson's views. Stanton had already undermined Johnson to some extent, telling Grant he could still continue to impose martial law in the South as needed even after Johnson declared the war officially over, raising the question of whether martial law was still legal. Stanton also vowed to stay in office, saying he considered Johnson to be a man "led by bad passions and the counsel of unscrupulous and dangerous men."

Dismissal of Stanton

Edwin Stanton (Source)

In January 1867, Republican Representative James Ashley of Ohio made the first formal move toward impeaching the President by proposing an inquiry into Johnson's official conduct. He made a number of allegations against Johnson, including suggestions that he had had a role in Lincoln's assassination and that he had sold pardons to former rebels, but offered no proof for these accusations. In June, the House Judiciary Committee voted 5-4 against approving any articles of impeachment.

However, the Republican attitudes toward Johnson soon hardened. During a congressional recess in August, Johnson took the opportunity to remove some of the more vigorous Reconstruction commanders from their posts. He also asked for Stanton to step down, declaring that "public considerations of a high character constrain me to say, that your resignation as Secretary of War will be accepted." Stanton shot back, "Public considerations of a high character, which alone have induced me to continue at the head of this department, constrain me not to resign." Johnson responded by suspending Stanton and appointing Grant as an interim war secretary in the hopes that he would be more aligned with his views.

In November 1867, the Judiciary Committee reversed itself and approved an impeachment resolution in a 5-4 vote. Representative John Churchill of New York said several matters in recent months had swayed him, including Johnson's statements denouncing Reconstruction efforts, his veto of a third Reconstruction bill, his dismissal of military officers overseeing Reconstruction, and his suspension of Stanton. The majority report made a number of criticisms of the President, saying his lenient attitude toward former rebels was helping to stoke violent incidents in the South, such as a race riot in New Orleans that killed scores of black men demanding the right to vote.

But the report was fairly general in its denunciations. Representative Thomas Williams, the Pennsylvania Republican who chaired the Judiciary Committee, said he did not think impeachment was possible under the circumstances of Johnson's alleged misdeeds as well as the constraints of the Constitution. Although 57 Republicans favored the impeachment resolution in a vote before the full House, 68 joined with 38 Democratic colleagues to oppose it. Another 22 congressmen did not vote on the measure.

On January 11, 1868, the Senate made a move to return Stanton to his post. In a 35-6 decision, they voted to restore him as Secretary of War. Grant did not protest the decision, and soon became embroiled in a battle with Johnson over the question of whether he had supported the President's effort to unseat Stanton. Grant charged that Johnson had sought his help in violating the Tenure of Office Act. This brought on another impeachment effort, led by Stevens, but the Committee on Reconstruction tabled this measure in a 6-3 vote.

Johnson was still itching to get Stanton out of his Cabinet. He offered to name the renowned Civil War general William T. Sherman as an interim War Secretary, but Sherman declined. On February 21, he settled on Adjutant General Lorenzo Thomas, an opponent of Stanton. Johnson issued one letter appointing Thomas as the interim Secretary of War and a second informing Stanton that he had been removed from office.

Instead of leaving, Stanton ordered Thomas arrested for illegally taking office. He quickly found support from the Republicans in Congress. A Senate resolution, passed in a 29-6 vote, stated that Johnson's action was beyond his power.

Once Thomas was released on bail, he too firmly held that he held the legal right to the office. For a time, the country essentially had two Secretaries of War. Many veterans and militiamen vowed to uphold the legitimacy of one man or the other, sparking fears that the squabble might lead to violence.

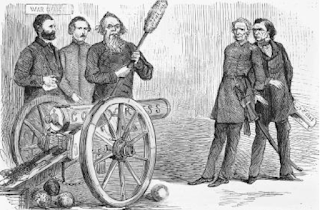

A political cartoon showing Stanton preparing to attack Johnson and Lorenzo Thomas, using a cannon labeled "Congress" and the Tenure of Office Act as a rammer. (Source)

The attempted removal of Stanton proved to be enough to get an impeachment effort off the ground. Some in Congress sided with Johnson, accusing the Radical Republicans of overstepping their authority and inflaming sectional divides, but the majority held that Johnson had been the one to exceed the power of his office. On February 24, the House of Representatives voted 126-47 to pursue impeachment. The confrontation with Stanton was the inciting issue, although Stevens suggested that Johnson had also bribed Grant by offering to pay any fine levied against him for violating the Tenure of Office Act by serving as Secretary of War.

There were some suggestions that impeachment was unnecessary. Johnson had no hope of capturing the GOP's presidential nomination, which Republicans expected would go to Grant, so the President had just over a year left in office. "Why hang a man who is bent on hanging himself?" Horace Greeley asked in the New York Tribune. For the Radical Republicans, however, a greater issue was at stake. Johnson could easily wreak havoc on the Reconstruction efforts in his final year in office; by removing him, they would remove that threat.

Impeachment

On March 2, the House of Representatives approved the first article of impeachment against Johnson. Two more articles were passed the next day. Ultimately, the House would seek to remove Johnson based on 11 offenses. It was the first time a President had been impeached. The Constitution states that impeachment can take place if an official is found guilty of "treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors;" it would fall to the Senate to decide whether Johnson's behavior was enough to convict him on any of the charges and remove him from office.

Nine of the articles of impeachment were essentially different ways of accusing Johnson of violating the Tenure of Office Act. The tenth listed a number of inflammatory comments Johnson had made about Congress, charging that the remarks "brought the high office of the President of the United States into contempt, ridicule, and disgrace." The final article was a general summary of the charges against Johnson.

There were enough Republicans in the Senate to convict Johnson on any one of these articles of impeachment and remove him from office. But there was also a certain degree of reticence among the GOP senators. The office of Vice President had been vacant since Johnson was sworn in; as president pro tem of the Senate, Benjamin Wade would be next in line to be President if Johnson was removed. Some Republicans were less than enthusiastic about this possible accession, since they saw Wade as being too liberal on Reconstruction issues to prevail in the upcoming presidential election; others disagreed with Wade's economic policies, which included support for high tariffs.

Chief Justice Salmon Chase, who had sworn Johnson in just a few years earlier, would now oversee the impeachment trial in the Senate. Johnson did not attend personally, but spoke to the press on several occasions to offer remarks on the proceedings. Representative Benjamin Butler of Massachusetts, a former Civil War general, led the prosecution. Attorney General Henry Stanbery resigned to lead Johnson's defense team,which included three other lawyers who volunteered their services.

An illustration of an impeachment hearing for Johnson (Source)

Butler called 25 witnesses during the trial. The crux of his argument was that Johnson had acquiesced to the Tenure of Office Act by initially following it, but then knowingly violated it by removing Stanton from office. He also blamed Johnson for the unrest in the South, saying his lenient attitude toward former Confederates had emboldened white racists into making violent attacks on black residents and others.

However, Butler also made a number of missteps over the five days of presenting his case. One passage earned a good deal of criticism by telling the senators that they were "bound by no law, either statute or common," but were rather "a law unto yourselves, bound only by natural principles of equity and justice." The prospect of a trial to decide the fate of the President was so exciting that public admission to the galleries was by ticket only, but the testimony soon became tedious. One press account declared the fourth day of Butler's prosecution to be "intensely dull, stupid, and uninteresting."

An admission ticket to the impeachment trial for Johnson (Source)

Johnson's attorneys figured that the nine Democrats and three pro-Johnson Republicans in the Senate would vote for acquittal. In order to deprive the vote of the two-thirds majority necessary to convict Johnson, they would need to convince seven Republicans to vote against impeachment. The defense called 16 witnesses to support its case.

The defense focused on the validity of the Tenure of Office Act. Johnson's lawyers argued that the President had no obligation to retain Stanton since he wasn't Johnson's own appointee. Ben Curtis, a former Supreme Court justice and one of Johnson's defenders, pointed out how the bill initially didn't extend to Cabinet officers. The defense also suggested that Johnson may have simply misinterpreted the law, and that he had the right to test the constitutionality of the Tenure of Office Act and have the matter heard before the Supreme Court. Thomas, they reasoned, had simply been appointed to keep the War Department staffed in the interim. The defense also suggested that the impeachment effort against Johnson wasn't motivated by any serious "high crimes and misdemeanors," but rather by the rancorous relationship between the President and Congress.

In the midst of the proceedings, Johnson consulted with his supporters and decided to blunt the impeachment effort by naming a compromise candidate as War Secretary. On April 21, he offered the position to General John Schofield, a Civil War commander who had been helping to oversee the Reconstruction efforts. Another Johnson lawyer, William M. Evarts, promised that Johnson would cease his efforts to impede the Radical Republicans' policies on Reconstruction if he was acquitted.

The Senate took their first vote, on Article XI, on May 16. This was the catch-all summary of Johnson's misdeeds, and the tally was 35-19 in favor of conviction. It was one short of the two-thirds majority necessary to convict; the defense had been successful in swaying seven Republicans to their side. One GOP representative, James Grimes of Iowa, summed up his opposition by saying, "I cannot agree to destroy the harmonious workings of the Constitution for the sake of getting rid of an unacceptable President."

Ten days later, the Senate voted on the first and third articles of impeachment to see if any of the opposing Republicans had been swayed by the prosecution's arguments on the Tenure of Office Act. Both votes failed to convict Johnson in the same 35-19 split. As it appeared that the divide would not change on any of the remaining eight articles, no further votes were taken.

The narrow margin of the acquittal raised suspicions that bribery had been employed to convince just enough senators to vote against conviction. Butler set up an impromptu committee to investigate the matter, interviewing dozens of witnesses and confiscating correspondence and bank records. The committee seemed particularly interested in Edmund Ross, a moderate Republican who had cast the deciding vote against conviction, but the committee ultimately finished its work without presenting any evidence of bribery.

End of term and later life

Following Johnson's acquittal, Stanton stepped down so Schofield could continue working as an undisputed Secretary of War. Johnson continued to spar with the Radical Republicans, vetoing bills related to Reconstruction and earning condemnation for his failure to provide federal protection for black residents and white Unionists who were subject to violent attacks in the South.

Although Johnson harbored no expectations that the Republicans would support him as their presidential pick for the 1868 ticket, he did believe that the Democrats were likely to choose him. Instead, they selected Governor Horatio Seymour of New York. A disappointed Johnson endorsed to be his successor. Grant was chosen as the Republican nominee and easily won the election.

The Tenure of Office Act was sidelined during Grant's presidency, with Congress giving him the ability to fire Cabinet appointees and lower level officials without Senate approval. The act was repealed in 1887, during the presidency of Grover Cleveland. The Tenure of Office Act was referenced several decades later when the Supreme Court took up the case of Myers v. United States. In a 6-3 decision in 1926, the justices ruled that President Wilson had the authority to remove a postmaster from office without Senate approval and that the Tenure of Office Act had been unconstitutional.

Returning to Tennessee, Johnson was soon vying to return to politics. Running as a Democrat, he was an unsuccessful candidate for the Senate in 1869 and the House of Representatives in 1872. He was successful in his next bid for Senate, in January 1875, becoming the only President so far to return to serve in this chamber.

Lincoln's other Vice President, Hannibal Hamlin, was also a member of this Senate, along with several of the same people who had tried to oust him from the White House seven years earlier. After taking the oath of office, Johnson denied rumors that he would try to fulfill any sort of vendetta against these senators. "I have no enemies to punish nor friends to reward," he declared.

Johnson's time in the Senate was short-lived. He served only from the start of his term on March 5 to the end of a special session on March 24. On July 31, at the age of 66, he died of a stroke near Elizabethton, Tennessee.

Sources: The Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, The National Governors Association, "Andrew Johnson, 16th Vice President" at Senate.gov, Andrew Johnson National Historic Site (National Parks Service), "The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson" at Senate.gov, Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson by David O. Stewart, The Presidents of the United States by Frank Freidel and Hugh Sidey, The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson by Chester G. Hearn, Andrew Johnson by Kate Havelin, The American Presidency, edited by Alan Brinkley and Davis Dyer, Reconstruction: A Historical Encyclopedia of the American Mosaic edited by Richard Zuczek