Tuesday, June 22, 2010

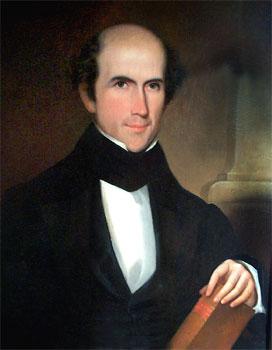

Benjamin G. Harris: two dollar treason

When several Southern states broke off from the Union following Abraham Lincoln's election as President, a sizable portion of people in the North were fine with letting them go. Their demands for peace grew louder as the war to preserve the Union grew longer and deadlier. Though government officials were largely behind the war effort, some demanded peace on the floor of Congress. One such representative, Democrat Alexander Long of Ohio, made such a speech on April 8, 1864, advocating recognition of the Confederacy. He accused Lincoln of scheming to start the war by provisioning Fort Sumter in South Carolina, leading to a Southern attack on the outpost and the subsequent start of the war. Long also opined that after three years of conflict, the only options left for the country were complete subjugation and extermination of the South or recognition of the Confederate States of America as an independent nation. Such talk was not well-received, and the House of Representatives took up discussion the next day on whether to expel Long for treasonable utterances.

Benjamin Gwinn Harris, a Democratic representative from Maryland, came to Long's defense during discussions the next day. He declared that he had long been the only member of the House favoring peace with the South via recognition, and welcomed Long as "another soul saved." Harris also announced his support for slavery and said he had owned slaves until Union general Benjamin Butler seized them. He said the Bible sanctioned slavery, and that the argument of abolitionists that slavery was an odious practice transferred the label onto "honest and upright men" who owned slaves, such as himself and his deceased father. "You may consider it a sin as between you and your God," he said, "but you shall not use insulting language upon such a subject as that without being called to account."

The congressional record shows that Harris's speech was met with quite a bit of derisive laughter, particularly when he said his peace stance made him more pro-Union than the other men in the chamber. "I am not here for war, and will not be here for war, so long as I have a heart humane and Christian, when war is carried on upon such principles. No, sir, war never did and never will bring your Union together in such a manner as to be worth one cent," he said. "I am for peace, and I am for Union too. I am as good a Union man as any of you. I am a better Union man than any of you." What truly got Harris in trouble, though, was his remark that the Confederacy "asked you to let them go in peace. But no; you said you would bring them into subjection. That is not done yet, and God Almighty grant that it never may be. I hope that you will never subjugate the South."

While the rest of his speech only earned him contempt, this portion led to a call for Harris to be expelled. Democrat Fernando Wood of New York declared during the ensuing tumult that the House should throw him out as well, since he fully endorsed Long. Though Elihu Washburne, a Republican from Illinois who supported the expulsion measures, promised to put Wood out as well, no vote was ever taken on that representative.

The vote to expel Harris narrowly missed the two-thirds majority needed to do so. Eighty-four were in favor of the action, while 58 were opposed. The House then took up a particularly strongly worded resolution to censure him. Declaring that he had made treasonable statements and committed a "gross disrespect to this House," the action sought to have him "very severely censured" and declared "an unworthy member of this House." The action carried 98 to 20, after an unsuccessful attempt to table the resolution and two failed efforts to adjourn. Long was also censured in a resolution declaring him an "unworthy member of this House" in an 80-70 vote on April 14.

The incident was the first time that Harris, an unabashed secessionist, got in trouble in the House for his actions. Born in Leonardtown, Maryland in December of 1805, he attended Yale University in Connecticut and the Cambridge Law School in Massachusetts. He wasn't admitted to the bar until 1840, and by that time he had already been a member of the Maryland house of delegates in 1833 and 1836. He was elected to the House of Representatives in 1862, and the censure didn't stop him from returning at the 1864 election.

Harris got in even more hot water when the war ended in Confederate defeat exactly one year after his censure. On April 26, 1865, former Confederate soldiers Richard Chapman and William Read visited Harris at his home. The two paroled soldiers asked Harris to stay at his residence, since they were going to another location on a pass but had grown tired. Harris was reluctant to accept the soldiers, given his position in the government and the Union suspicions his sympathies to the Confederacy had earned him. Instead, Harris gave the men a dollar each for lodging. They stayed at a place about a mile and a half away, using the money for the evening's shelter and a meal.

Harris was surprised when in May he was arrested on a charge of harboring the Confederate soldiers. The real motivation for the arrest, however, lay in the discussion he had with the soldiers at his doorstep. He was charged with not just giving the soldiers money for a roof over their head, but advising them to keep up the fight for the Confederacy. The penalty for such disloyalty could be as severe as death.

Harris was quickly court-martialed by the War Department and tried in a military court in Washington, D.C. In addition to relieving the two Confederate soldiers with money, the court charged, Harris was charged with "advising and inciting them to continue in said army, and to make war against the United States, and emphatically declaring his sympathy with the enemy, and his opposition to the Government of the United States in its efforts to suppress the rebellion." Harris protested that a court-martial was not appropriate, since he was in no way connected with the U.S. armed forces. He admitted that he gave the soldiers the money to pay for lodging so he wouldn't get into trouble with the authorities. He also said it had already been proven that the soldiers were not lodged where they said they had bunked down for the evening.

Chapman confirmed that Harris had been reluctant to lodge them due to scrutiny by federal authorities. A native of Baltimore, Chapman left the loyal state of Maryland to join the Confederate Army. As per the surrender arrangements, soldiers who had deserted the United States to fight for the South needed to take an oath of allegiance to the United States before they were allowed to go home. Chapman, who lost five brothers to the war, said he would go home to Baltimore if he could take the oath. Harris said that Chapman could go wherever he wanted since he was on parole, and Chapman replied that he'd seen a notice saying the oath was a requirement. Harris bitterly responded that paroled soldiers ought to be able to go home anyway and that Union general Ulysses S. Grant was a "damned rascal" if he didn't allow it.

Chapman said Harris got much more expressive on the state of affairs in the nation, praising the cause of the Confederacy as just and Confederate president Jefferson Davis as a great leader and true Southern gentleman. He suggested that Chapman not take the oath, since he was sure many other soldiers would refuse it, but instead be exchanged to keep up the fight for the South. Perhaps worst of all, during a discussion of Republican President Abraham Lincoln's assassination Harris commented that the death had come too late to do the rebels any good. Read also recalled that Harris was reluctant to lodge the men but urged them to keep fighting for the Confederacy. A Union sergeant who arrested Harris said that the congressman had admitted to giving the soldiers money. Though he hadn't admitted that he urged the men to keep fighting, he did complain that the abolitionists were interfering too much with post-war affairs.

Harris was swiftly found guilty of violating the 56th article of war and sentenced to three years in prison. Though this conviction forever disqualified from holding any office in the United States government, a reprieve came within weeks. President Andrew Johnson, Lincoln's Republican successor, issued an executive order on May 31 approving, confirming, and then remitting the sentence. Johnson said the order to remit was due to "additional evidence and affidavits...bearing upon this case and favorable to the accused, having been presented to and considered by me, since the sentence aforesaid."

Harris was released and allowed to return to Congress. At the commencement of a session in December, Republican Representative John F. Farnsworth asked the Committee on Elections to look into Harris's qualifications for the seat. He cited the court-martial, sentence disqualifying him from office (which he argued had been confirmed by Johnson but not remitted), and the statements about Lincoln's assassination as being inconsistent with the oath of office. The committee never reported back, and the House never took a vote.

At the expiration of his term in March of 1867, Harris left Congress for private life. However, he periodically made public statements on the dead cause of slavery. In September of that year, he strongly opposed a new state constitution for Maryland on the argument that it conceded too much to liberal Republicans by abolishing slavery and conforming to the Civil Rights Bill, which declared "that no person shall be incompetent as a witness on account of race or color, unless hereafter so declared by act of the General Assembly." The constitution, he said, was an "abomination" and would "place us on an inclined plane which leads directly and irresistibly to the foul slough of radicalism." That same year, the New York Times described him as "the representative man of the old pro-slavery Democrats yet alive in the state."

In 1874, Harris unsuccessfully sought the Democratic nomination for his district's House race. Here, he focused on the Fourteenth Amendment (which included citizenship for any person born in the United States, enforcement of civil rights, and prohibitions against elected officials who took an oath of office and joined the Confederacy) and the Fifteenth Amendment, which gave voting rights to former slaves. Both amendments, Harris said, were "utterly void."

In 1892, at the age of 86, he was still beating the same drum. In that year, he sent a petition to Congress on behalf of himself and other residents in Maryland asking to be compensated for slaves who had been freed by state or federal law.

Harris died on his Leonardtown estate in April of 1895.

Sources: The Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, "A Member Of Congress In Trouble" in the London Evening Advertiser on May 3 1865, "Treason At Home" in the New York Times on May 5 1865, "Treason At Home" in the New York Times on May 7 1865, "Treason At Home" in the New York Times on May 13 1865, "The Case Of Benj. G. Harris" in the New York Times on Jun. 5 1865, "Hon. Benjamin Harris On The New Maryland Constitution" in the New York Times on Sep. 12 1867, "Maryland" in the New York Times on Oct. 26 1867, "General Notes" in the New York Times on Jun. 14 1874, "Contested Election" in the Deseret News on Jun. 27 1874, "Wednesday In Washington" in the New York Times on Mar. 24 1892, Reports of the Committees for the House of Representatives for the First Session of the Forty-Third Congress, On the Resolution to Expel Mr. Long speech by Benjamin G. Harris, The Dark Intrigue: The True Story of a Civil War Conspiracy by Frank Van Der Linden, The Great Conspiracy: Its Origin and History by John Alexander Logan, The House: The History of the House of Representatives by Robert Vincent Remini, The Political History of the United States During the Great Rebellion by Edward McPherson

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment