Saturday, April 3, 2010

Marshall Tate Polk: almost south of the border

The conclusion of the attempted flight of Marshall Tate Polk Jr. from the country sounds like it could have inspired a Wild West movie. Running from charges that he'd stolen funds from Tennessee while acting as the state's treasurer, Polk wound up on a train making its way through Texas. The conductor of his sleeping coach happened to recognize him from the notices posted along his likely route. Once Polk got off at a station, the conductor disembarked as well, gathered a companion, and told another person to contact the authorities. The conductor then took off after Polk, who had left with his servant on horseback.

The conductor and his friend gave chase. Somewhere in the Texas scrub, the conductor managed to get the drop on Polk, stepping out from behind a bush to confront him. Both Polk and his servant pulled their revolvers on the intruder, but the conductor remained steadfast. He warned that the surrounding countryside was crawling with rangers. "Put up your guns, or I'll have your heads blown over into Mexico," the man warned. Sufficiently intimidated, both Polk and his servant handed over their weapons. It was a bold maneuver, and one that paid off well. The conductor had been unarmed until the two men surrendered their guns, and he and his companion promptly used the revolvers to hold the two men until the rangers actually arrived.

Most of these details come from a New York Times article featuring the conductor's story, so it is quite possible that the trainman chose to embellish the details. The underlying facts are sound, however. Suspected of embezzling hundreds of thousands of dollars in state funds, Polk had been riding the rails through Texas. And he was indeed captured not far from the Rio Grande while fleeing with his servant on horseback.

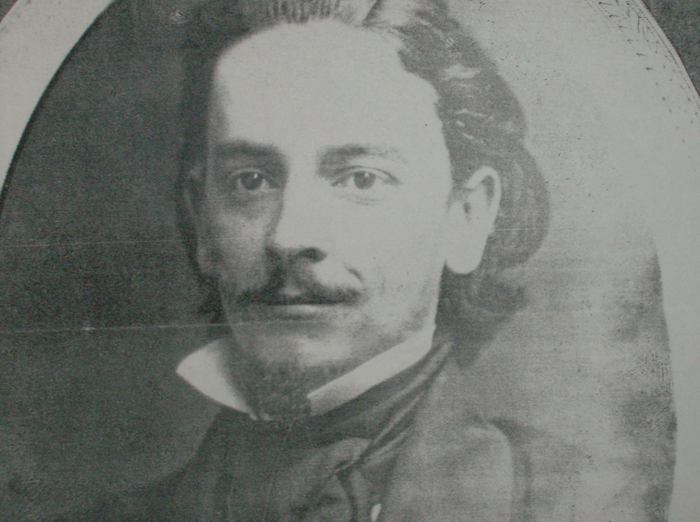

Marshall Polk, who sometimes went by the abbreviated name M.T. Polk, was also somewhat notable due to his relationship to a former President. Polk's father died about a month before he was born in Morgantown, North Carolina, in May of 1831. His uncle, James Knox Polk, was a U.S. Representative from Tennessee at the time, and he took his nephew under his wing; this elder Polk would go on to be the Governor of Tennessee and eleventh President of the United States.

Marshall Polk attended Georgetown University, and graduated from West Point in 1852. He joined the Confederate army during the Civil War as a captain of artillery, and was seriously wounded at Shiloh. The injuries were bad enough that he had to have a leg amputated, but he remained in the service and was promoted to colonel, serving on the staff of General Leonidas Polk (presumably another relative). After the war, Marshall Polk lived on a farm near Bolivar, Tennessee and published the Bolivar Bulletin. He first entered the political field in 1876 by attending the Democratic National Convention as a delegate, and the next year he began serving the first of three terms as Tennessee state treasurer.

It was later determined that Polk had been embezzling for five of his six years in office. The action most cited after the discovery of this crime was the One Hundred and Three Funding Bill to settle the state debt. Polk was given $600,000 to pay interest on the bill, but left in possession of the money after an injunction was started and the bill declared unconstitutional. It was also mentioned that Polk had another $400,000 under his control when the actions regarding the bill took place. As a customary inspection was about to take place in January of 1883, Polk quietly disappeared from the state. The study found that hundreds of thousands of dollars were missing, mostly due to the lack of caution in the banks where the state funds were deposited. Polk had managed to deposit several checks, despite the fact that they lacked the signature of the state controller. With this lack of oversight, it wasn't difficult for the treasurer to withdraw the funds for his own personal use.

When it became clear that Polk had absconded from the state, the Tennessee house of representatives considered offering a $20,000 reward for his capture. That idea fell through after one legislator said the treasurer had nothing with which to repay the state, and so the reward would only add to the financial burden caused by the embezzlement. Polk's bond was good for $100,000, something of a small amount considering the amount of money he had control over. There had been a proposal in the legislature to increase the bond, but the bill had been stolen from the desk of the state senate clerk the day before it was supposed to go to a final vote. In the wake of the embezzlement, the legislature resolved to seize Polk's assets and thoroughly examine the state's books to find if anyone else was involved in the theft. In the midst of the upheaval, reform proposals come fast and heavy in the legislature. They included suggestions to increase treasurer's bond to $500,000 and have the treasurer make a monthly report to the Governor, controller, and secretary. Another proposal would have the treasurer deposit funds in banks with sufficient bond coverage within three days of receiving them, with the checks countersigned by the Governor and controller and marked to show what they would be used for.

Captain James Fleming, Polk's clerk and bookkeeper, helped investigators determine how the money went missing. One popular suggestion was that Polk had diverted considerable funds to political allies, and newspaper reports anticipated further criminal charges. Despite his cooperation, Fleming was arrested the next year as he was tried to leave the state. He was accused of making false entries totaling $40,000 on behalf of Polk, but the case faded from the public eye soon after. It seems no other potential co-conspirators, estimated to number about half a dozen when the scandal first broke, were charged. "Throughout the city in circles where Mr. Polk was known and liked for his generosity, there is universal regret at his disgrace which has come upon him, and perhaps no man's fall was ever more generally regretted," the New York Times declared.

Polk's point of destination was more obvious than that of the Kentucky treasurer who shared one of his names and would take flight five years later. Mexico not only contained a silver mine owned by the treasurer, but also had no extradition policy with the United States. Warrants of arrest were sent to cities along his probable escape route. Polk's wooden leg would provide a ready clue for law enforcement authorities. Five days after his departure on January 2, it was announced that he had been arrested in San Antonio, Texas by a Pinkerton detective.

Much to the horror of authorities and citizens in Tennessee, Polk got away again. The one-legged man claimed he was not Polk, but his cover story wasn't exactly convincing. He gave his name as "Tate" and said he was simply a wealthy man going to look over his mining interests. Outgoing Democratic Texas Governor Oran M. Roberts said he had no authority to hold Polk unless someone made a charge against him while under oath, and the detective said he had no authority to hold the man. When Polk was finally arrested again, about 18 miles shy of the Rio Grande, the detaining marshal suggested that the treasurer had paid off the Pinkerton detective. At the time of his arrest, Polk had several state checks with him.

As Polk was being returned to Nashville, the legislature appointed attorney Atha Thomas as a replacement on the 22nd ballot. Polk told reporters on his arrival that several reports about his journey were false, including allegations that he had been drinking heavily the entire time. He also seems to have tripped over his words, saying both that he was taking a routine trip to Mexico to check up on the mine and that he intended to raise the defaulted money in order to repay the state in full. The same month that saw Polk's defalcation revealed and his subsequent dash for the border also brought his indictment, which charged that he acquired $484,000 from the state treasury through embezzlement and larceny.

An investigation determined that by 1878, about a year into his job, Polk was defaulting $20,000 to $40,000. By April of 1882, the amount was up to $216,520. The probe blasted the banks involved in the case, since they had extended false credit to Polk. In doing so, committee members determined, the banks had failed to stop the embezzlement when they could have staunched the loss at only $200,000. The banks had honored several checks not countersigned by the state controller, and Polk had distributed the money in several ventures. These included $50,000 for the silver mine, $10,000 to the Nashville American publishing company, and investments in North Carolina lumber and Alabama iron. He also loaned money to Democratic politicians.

Fortunately, Polk's theft was softened by both the attachments against his property and $150,000 which was legitimately owed to him by various people. In February of 1883, his friends proposed a payment schedule to free Polk and the state from debt, but it came to naught. The next month, however, the legislature passed an act allowing settlement. It said Polk could pay $100,000 on genuine bonds and another $150,000 on internal improvement bonds. When paid, the sureties against his property would be relieved. The act specifically stated that the settlement would not absolve him from criminal prosecution. By late June, Polk's friends had paid $75,000 toward the settlement, and there were rumors that the prosecution could be dropped. However, Polk had been arrested again only the month before. He had been granted release due to health reasons, but a $20,000 bond he had given was found to be insufficient and he was suspected of making another run for it.

Polk's trial began in June of 1883. The case was well-known enough that over a thousand people were rejected for jury duty, since they knew all about the matter. A panel was finally assembled from 12 illiterate country bumpkins. An Iowa newspaper, the Carroll Herald, clearly clearly took exception to the claim that an intelligent body had been chosen. "Tennessee has about as much reason to be proud of this phenomenal jury as of the criminal it is to try," the article sniffed. It didn't matter much in the end, as the entire jury was dismissed and a new one assembled before the trial was through. There were lingering concerns about the ability of the jurors to fairly hear the case, with one member in particular having been employed by the widow of former President Polk.

Defense attorneys argued that Polk was only guilty of "default of pay." They said large deficits against the treasurer were common enough, and could be explained through legal reasons consistent with the treasurer's duties. They added that $50,000 had already been put into the state via sureties, with another $10,000 on the way and significant sums available through the sale of the silver mine and lumber interests. The lawyers said the jurors needed to give the ex-treasurer a chance to make good the defalcation. "If he has got that money in his pocket, you can't send him to prison without first giving him a chance to pay it," they said. "He cannot be accused of refusing to pay when no one has demanded of him to pay." The jury agreed with the prosecution's assessment that Polk's actions were embezzlement through and through. He was found guilty in July, and sentenced to serve 20 years in prison with a fine equal to the amount stolen.

In February of 1884, the New York Times reported that his sentence was only 13 years; this may have been a result of an appeal or an error on the paper's part. It added that his mining interests in Mexico had been sold for $2 million, and that his health was very poor. Two days after the article was published, with an appeal set to go before the Supreme Court, Polk died of heart disease in Bolivar, Tennessee. Even this latest development was in doubt, at least in some circles. In 1887, a report claimed that Polk may have faked his death. An Alabama citizen returned from Mexico, saying he had met Polk there. The item apparently did not gain much credibility, and it was not considered any further.

Sources: The Political Graveyard, "A Deficit In Tennessee" in the New York Times on Jan. 6 1883, "Empty Vaults" in the Aurora Daily News on Jan. 6 1883, "Polk Still A Fugitive" in the New York Times on Jan. 7 1883, "Treasurer Polk Arrested" in the New York Times on Jan. 8 1883, "Treasurer Polk Escapes" in the New York Times on Jan. 9 1883, "Treasurer Polk Recaptured" in the New York Times on Jan. 10 1883, "Treasurer Polk's Recapture" in the New York Times on Jan. 13 1883, "Some Of Polk's Methods" in the New York Times on Jan. 13 1883, "Ex-Treasurer Polk Indicted" in the Reading Eagle on Jan. 14 1883, "How The Conductor Captured Polk" in the New York Times on Jan. 15 1883, "Ex-Treasurer Polk's Friends" in the New York Times on Feb. 22 1883, "Settling With Polk" in the New York Times on Mar. 24 1883, "M.T. Polk Again In Jail" in the New York Times on May 4 1883, "Polk's Case To Be Called" in the New York Times on Jun. 25 1883, "Marsh T. Polk On Trial" in the New York Times on Jun. 27 1883, "A New Jury To Try Polk" in the New York Times on Jul. 4 1883, "Polk On Trial" in the New York Times on Jul. 16 1883, "The Polk Trial" in the New York Times on Jul. 22 1883, "Was It A Farce?" in the New York Times on Jul. 23 1883, untitled brief in the Carroll Herald on Jul. 25 1883, "Ex-Treasurer Polk, Of Tennessee" in the New York Times on Feb. 27 1884, "Death of Ex-Treasurer Polk" in the New York Times on Mar. 1 1884, "Mr. Polk Is Living" in the Meriden Daily Republican on Sep. 6 1887, The Banker's Magazine and Statistical Register Volume 37, James K. Polk: A Biographical Companion by Mark Eaton Byrnes

Labels:

disappearance,

embezzlement,

Marshall T. Polk,

Tennessee,

treasurer

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

4 comments:

tionnish ymeneloin regards to my grandfather...I really doubt that he was out-witted by a railroad conductor..thats funny.During this time period many ex-Confederates in public office embezzled money,many..and most of it went to the people of the South,poor broke ex-Confederates who were being literally "raped" by a Pro-Union puppet govt.I doubt my grandfather died as stated...I personally think he quietly disappeared as he had many,many friends..

I have a photo of his grave site I think taken around 1911 if anyone is interested. We are the descendants of the L.L. Polk family in Raleigh, N.C. Jay Denmark

I doubt he had been out smarted by a conductor. lol. As a descendant from this Polk tree, this is a great story. I have told people that my great great great grandfather was President Polk even though he never had children due to his sterilization. I consider President Polk my grandfather because Marshall Tate Polk was raised by President Polk soon after Marshalls father died soon after his birth.

jbird919, I would love to see the photo. I am a descendant of Ezekiel Polk through his daughter, Matilda Golden Polk Campbell.

Post a Comment